If you design the groove, specify the seal, or troubleshoot leakage—this is for you.

Shore A hardness is a useful control parameter, but by itself it is not a sealing strategy.

Seals don’t fail because “55 Shore A was wrong.” They fail because the joint did not generate and maintain the required contact pressure across tolerances, temperature, time, movement, and assembly realities.

Hardness is one input. Sealing is a system outcome: design × compound × cure × installation × environment.

1) What hardness actually controls (and what it doesn’t)

Hardness influences

- Contact pressure at a given squeeze (harder → higher contact pressure for the same compression, up to a point)

- Conformability (softer → fills micro-gaps better; tolerates rough/uneven surfaces)

- Assembly force & friction tendency (hardness affects it, but geometry and surface often dominate)

- Stability in the groove (harder carriers resist creep and pull-out better)

Hardness does not reliably predict

- Compression set (a 70A compound can have poor CS; a 55A can be excellent)

- Long-term sealing retention (stress relaxation + joint design dominate)

- Leak tightness by itself (geometry + squeeze + tolerance variation matter more)

2) The 4 variables that should drive hardness selection

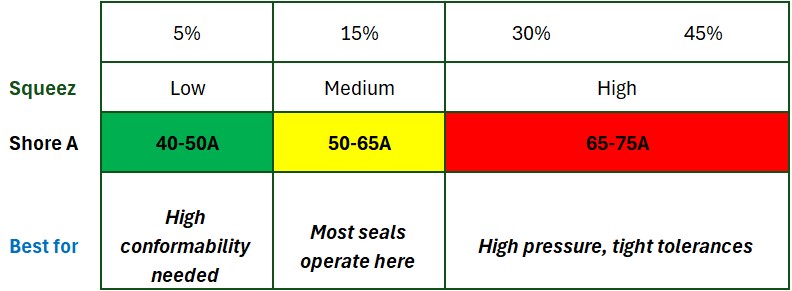

A) Squeeze % (the first “real” spec)

Squeeze = how much the seal is compressed in the joint.

- Low squeeze (5–15%) → needs high conformability or geometry that concentrates contact pressure

- Medium squeeze (15–30%) → most seals live here

- High squeeze (30–45%+) → risk of high assembly force + long-term set if not designed carefully

Key point: For a given geometry, hardness is your dial to reach target contact pressure within your squeeze window.

B) Contact pressure requirement (what you’re really buying)

A seal leaks when contact pressure is lower than the forces that open micro-leak paths:

- internal fluid/air pressure

- joint roughness, parting lines, tolerance gaps

- deformation under service load

This is why 70A can leak: if squeeze is limited or the geometry doesn’t load correctly, you get inadequate contact pressure where it matters.

C) Friction & assembly force (the hidden failure mode)

A seal that seals in theory but cannot be assembled consistently becomes a production failure:

- seals are stretched, twisted, installed dry, or damaged

- seating is incomplete (and leakage appears “unexplained”)

Hardness influences force, but surface tack, lubrication strategy, and groove geometry often dominate.

D) Tolerance stack-up & movement (static vs dynamic)

- High gap variation → softer seals maintain contact better

- Dynamic sliding → too soft can increase wear and frictional heat

- Pressure + extrusion gap risk → may require higher hardness and/or anti-extrusion support

3) Why 70A can leak and 55A can seal better (and vice versa)

Case 1: 70A leaks, 55A seals better

Typical when:

- squeeze is limited

- tolerance variation is high

- surfaces are rough/uneven

- geometry spreads load rather than concentrating it

Result: 70A may not conform enough to close micro-gaps at low squeeze; 55A can.

Case 2: 55A leaks, 70A seals better

Typical when:

- higher internal pressure or pressure peaks exist

- extrusion gaps are present

- seal must resist deformation to maintain contact pressure

Result: 55A deforms or relaxes too much; 70A holds shape and pressure.

Takeaway: Hardness is not “better or worse.” It is “matched or mismatched.”

4) The 40 Shore A zone: when soft seals are the right answer (and when they fail)

A) 40A solid O-cords / rings (static sealing, high conformity)

Works well when

- low-to-moderate pressure static sealing

- imperfect alignment, surface irregularities, slight ovality

- low assembly force + high conformity are required

Can fail when

- an extrusion gap exists (clearance + pressure)

- long-term compressive load drives stress relaxation and loss of contact pressure

- high stretch during fitment demands excellent elastic recovery

Practical guidance

- Use 40A when extrusion is controlled by design

- Validate sealing after dwell (24–72 hours), not only on day one

B) 40A hollow EPDM seals with splice joints (easy-fit / roll-fit)

Common pitfalls

- high friction/tack → difficult sliding/rolling → installation damage

- splice weakness due to localized strain

- compression drift when squeeze varies or stress relaxation is high

What to control

- friction/tack behavior (functional surface requirement)

- stress relaxation at service temperature

- splice design + cure matching

5) When one hardness can’t do two jobs: co-extruded seals (hard carrier + soft bulb)

Typical architecture

- Hard carrier (~65–75A, dense): retention, groove stability, pull-out resistance

- Soft bulb (~35–45, often sponge/foam): tolerance take-up, sealing at low force

Important note: For sponge, density + compression behavior often matter more than Shore A.

Define: density range + load-deflection at specified squeeze + recovery after cycling.

Validate: interface peel/tear strength, especially at corners/radii and after cycling.

| Application type | Typical pressure | Movement | Key risk | Starting hardness |

| Weather/dust/water exclusion | Low | Static | tolerance variation | 50–65A |

| Static gasket sealing (controlled squeeze) | Moderate | Static | relaxation + aging | 60–75A |

| Clamp sleeves / interference on metal | Low–Moderate | Mostly static | assembly damage vs creep | 55–70A |

| Dynamic wiping / sliding | Low–Moderate | Dynamic | wear + friction heat | 65–80A |

| Soft/high-conformity seals (O-cord, hollow bulbs, easy-fit) | Low–Moderate | Static | extrusion gap + relaxation + friction | 35–50A (only if extrusion is controlled) |

| Lock-fit + soft sealing requirement | Low–Moderate | Static/Dynamic | retention + tolerance | Co-ex: carrier 65–75A dense + bulb 35–45 sponge |

Rule of thumb: If extrusion gaps or pressure peaks exist, increase hardness and/or add anti-extrusion support—do not rely on softness alone.

7) Validation approach (how we de-risk field failures)

- Prototype two options (e.g., 60A and 70A; or 40A vs 50A)

- Validate using a joint-level fixture that matches squeeze/tolerances, surface finish, cycling, and installation method

- Track: seating consistency, assembly force, leak/ingress performance, recovery after cycling, and set/relaxation after dwell

This turns hardness selection from opinion into engineering.

If you’re defining a seal or troubleshooting leakage, share any two of the following and we can recommend a starting hardness strategy and minimum validation plan:

- joint sketch/photo or groove dimensions

- squeeze window / installed height range

- service temperature range + peaks

- media exposure (water/air/oil/cleaner/adhesive/paint)

- static vs dynamic movement

Our approach is simple: spec hardness as a control metric, but qualify sealing at the joint level—because that’s where failures (and reliability) are actually decided.